We Need To Go To War

By Alice Vachss

Originally published in PARADE Magazine, June 27, 1993

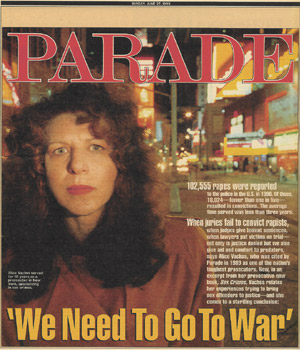

Police records indicate that one woman is raped every 6 minutes in America. Worse, experts believe that only 30 percent of rapes are ever reported. Women who do bring charges often find themselves victimized by the very criminal justice system designed to protect them. Alice Vachss—who was identified by PARADE in 1989 as one of the country's toughest prosecutors—has been on the front line of rape prosecutions. From 1982 until 1991, when she says she was fired for her refusal to make political accommodations, Vachss was an assistant district attorney in Queens County, N.Y., specializing in sex crimes. This excerpt from her new book, "Sex Crimes" (published this month by Random House), offers a tough, candid, behind-the-scenes look at the realities of bringing sex criminals to justice and tells the stories of courageous women who fought to put their attackers behind bars. The stories are true. Some of the names have been changed.

* * * * * *

THE FIRST SEXUAL OFFENDER I TRIED—Johnny Washington—was also the first felony trial for the judge who presided. At the initial conference between the judge, the defense attorney and me, the judge offered to let the defendant plead to the charges in exchange for a minimum sentence. I objected, but the judge ignored me. It was the defense attorney who turned down the offer. But in light of the judge's generosity, the defense attorney waived a jury—preferring to let this judge issue the verdict on the guilt of the defendant. Right then, I should have known.

THE FIRST SEXUAL OFFENDER I TRIED—Johnny Washington—was also the first felony trial for the judge who presided. At the initial conference between the judge, the defense attorney and me, the judge offered to let the defendant plead to the charges in exchange for a minimum sentence. I objected, but the judge ignored me. It was the defense attorney who turned down the offer. But in light of the judge's generosity, the defense attorney waived a jury—preferring to let this judge issue the verdict on the guilt of the defendant. Right then, I should have known.

Carmen was petite, dignified—and terrified when she took the witness stand. She testified that she had returned home from her job as a bank teller at around 6:30 in the evening. A stranger, later identified as Washington, had followed her onto the elevator in her apartment building. When Carmen tried to get off at her floor, the stranger grabbed her from behind. He told her he had a knife and that he would kill her if she didn't cooperate. At the roof, he dragged her over to an electrical shack, where he made her undress and lie down on the gravel. He covered her face with his jacket while he raped her and sodomized her. Then he made her give him her watch and money.

After he left her on the roof, she crawled down the outside of the building to her apartment. Her sister, a social worker who counseled rape victims, testified about seeing Carmen appear at her door, her clothes in disarray and scrape marks allover her back and legs. They called Carmen's boyfriend, who was a police officer, to take them to the precinct to make the complaint.

Four days later, Carmen saw Washington on the street and called the police. This is the man, she said, who raped her.

Unbelievably, the judge decided that because Carmen hadn't seen the rape, she couldn't be sure of the penetration. He wanted nauseatingly graphic details. I told the judge he was saying that a blind woman couldn't prosecute a rape case in Queens County. That quote was picked up by the media—with two results: Although the judge did not find Washington guilty of rape, he felt compelled to impose the maximum sentence on him for the lesser offenses, including first-degree sexual abuse; it added up to the same sentence as a rape conviction. And the judge hated me for life.

My first lesson about sex-crimes prosecution was that perpetrators were not the only enemy. There is a large, more or less hidden population of what I later came to call collaborators within the criminal justice system. Whether it comes from a police officer or a defense attorney, a judge or a prosecutor, there seems to be a residuum of empathy for sexual predators that crosses all gender, class and professional barriers. It gets expressed in different ways—from victim-bashing to jokes in poor taste, and too often it results in giving the sexual offender a break.

It didn't take me long to get the reputation of someone willing to take on any rape prosecution. Other trial attorneys "gave" me their sex cases. Mostly what I got were the ones nobody else wanted: cases in which the proof was weak or the victim unlikable—or simply cases that involved a lot of work.

The victim was a big, homely, unlikable teenager. She had a crush on one of the popular boys—a handsome athlete who was everything she wasn't. One night, she ran into him in the neighborhood. Probably she would have been willing to do anything he asked of her. Instead he forced her to have sex with him and his friend. If the term had been fashionable then, it would have been called date rape. He did it to be doing it, because he could, and who, he thought, would care?

He was almost right. Her family didn't care. Her brothers yelled at her for getting raped. Her mother wouldn't interrupt her bowling night to take the girl to the police precinct.

The victim, nevertheless, on sheer courage alone, went to the police. One of the rapists, the friend, was arrested. He went to trial. Sure enough, the jury didn't like the victim. She was sullen where she could have been sympathetic, unresponsive in cross-examination. She didn't expect a jury to believe her. She knew she needed to do this for herself. It made me angry. I tried the whole case angry.

And the jury convicted.

It was more than a year later before the co-defendant was found and arrested. I contacted the victim. She had built a new life for herself, met a man and had a son. She still was willing to prosecute. I put together enough of a case so that Mr. Popularity pleaded guilty. When I told the victim both rapists were in prison, she was happier than I thought she could be. She said when her son got older, she would tell him.

I'd like him to know that his mother taught me something about bravery.

Being a sex-crimes prosecutor meant, for me, eye witnessing courage. It was the one common denominator among the victims I had the privilege of accompanying into a courtroom to testify that they had been raped.

Other prosecutors in the office insisted on more common denominators than that. They wanted their rape victims to fit an image. How the jury responds to a victim is an enormous percentage of the verdict in any sex crimes trial—which is why prosecutors want "good victims."

In New York City, good victims have jobs (like stockbroker or accountant) or impeccable status (like a police officer's wife); are well-educated and articulate; and are, above all, presentable to a jury: attractive but not too attractive, demure but not pushovers. They should be upset, but in good taste—not so upset that they become hysterical.

Such attitudes not only are distasteful, they are also frightening. They say it's OK to rape some people—just not us.

Rapists tend to go to trial more often than any other kind of criminal, believing in their souls that all men, including those on the jury, would rape if they only had what it takes. They are supported too often in this belief by the fact that what the defense puts on trial is the victim.

People do say that anybody can be raped, that rapists don't discriminate. It is true that rape victims include among their ranks heiresses and nuns and great-grandmothers. But they also include crackheads and dope dealers, junkies, whores, thieves and liars.

Rapists do discriminate-they look for whatever vulnerability might insulate them from capture and punishment. Sometimes that means raping a child, because we seem as a country to doubt the word of children who say they've been raped. And sometimes that means trying to sell the rest of us on the concept that it isn't really rape if the victim is someone we don't like.

The one truth that is more important to me than all the rest is that what the public is entitled to from prosecutors is not any particular verdict but the willingness to step into the ring again and again.

I remember, for example, Terry Pittman. He didn't have in him what quality it is that makes the rest of us human. He'd lucked into a teenager who asked if he knew where to buy marijuana. He took her to his apartment and raped her. She struggled so hard she kicked out a window. He twisted her neck so violently that he paralyzed her. She begged: "Help me, help me, I can't move!" It aroused him, and he raped her again. When he was done with her, he dumped her, naked, on the driveway. Neighbors called the police.

The victim's parents didn't think she had the strength to prosecute. I did. I believed her when she told me, "If I have to testify, I'll testify—whatever it is—just so long as he gets punished." Pittman pleaded guilty. The day she could walk on her own again, with crutches, she came to the courthouse to find me. She brought me a rose.

From the beginning, I never had a caseload made up solely of sex crimes. I found out that not every rapist got charged with sexual assault. Rapists always knew what I had to learn: There is more than one way to penetrate a victim. People who think rape is about sex confuse the weapon with the motivation.

Robert Roudabush was charged with attempted murder. It was Christmastime. He was supposed to take his wife, Maureen, shopping for gifts. Instead he got drunk and stayed late at his office Christmas party. When she complained, they argued. He decided he knew how to settle it, once and for all. He went into the bedroom and assembled a minor arsenal-two rifles, a shotgun.

Maureen took her 1-year-old into the kitchen to prepare a bottle for him. She was standing at the refrigerator with the baby in her arms when Roudabush spoke from behind her: "Don't move, I'm going to kill you." As she turned instinctively toward the sound, he shot her. The first bullet lodged in her neck, near the spinal column. She and the baby both went down. That was why the other shots missed them. Roudabush kept firing until the rifle jammed.

She screamed for the neighbors to call 911. They took her in an ambulance. They took him in a police car.

Maureen later told me she had to keep phoning the DA's office from the hospital, insisting that her husband be prosecuted. They told her her husband would never be convicted. Besides, sooner or later she would drop the charges.

Maureen was terrified her husband would get out of jail and kill her. At a preliminary hearing, the judge believed her and kept her husband in jail. They gave the case to me.

Even after I started pushing, Roudabush's case stayed pending for almost a year. Maureen got divorced, moved in with her mother, waited. Maureen and I talked before and after each court appearance. I started each conversation telling her that her ex-husband's bail status hadn't changed. She needed to hear it. She still lived in fear.

Roudabush wrote to Maureen while he was in jail. He tried all the angles. One letter would declare his love and repentance and beg her forgiveness. The next would be full of threats. Some letters would tell her he'd found God. None of these worked. Finally, we went to trial.

There was more proof against Roudabush than I was used to having. Maureen was young, pretty and distraught, with her Irish-rose face radiating credibility. At one point in her testimony, she broke down in tears. I talked to her on the break, and she said, "I'm so scared of him. He's sitting looking at me, and I'm so scared the jury is going to let him go, and he'll kill me." The jury seemed to understand her feelings. In addition, there were recovered weapons, ammunition, a confession and injuries serious enough for a jury not to discount the crimes as "only" domestic violence. The People's case was persuasive, powerful—it felt like a conviction.

Then the defense called a neurologist as a witness. The defendant had a history, from birth complications through childhood epilepsy, the neurologist said, that together with a lifelong propensity toward sudden violence, led to a diagnosis of "episodic dyscontrol." According to the doctor, Roudabush did not "intend" his crimes. His episodic dyscontrol meant he had irresistible urges to commit violence—episodes of rage beyond his control.

Because the testimony came as a surprise to me, the judge gave me the weekend to prepare my cross-examination. I needed every minute of it. What the doctor said sounded logical, but its consequences were devastating. If he convinced the jury, Roudabush simply went free.

That Friday night was one of the lowest times for me that I can remember during a trial. What if the neurologist was right? But while I was worrying the problem to death, I had a moment of simple perception that felt like it applied to a lot more than one trial.

Monday morning, I cross-examined the neurologist for several hours. Then I delivered the payload question. If Roudabush suffered episodic dyscontrol, how come the only victim of his violence was his wife? How come he never had these fits at work or driving his car? The jury convicted. Roudabush did 10 years of a 6- to 18-year sentence before being paroled out of state. He hasn't had any incidents of "episodic dyscontrol" since the trial.

When I decided to become a sex crimes prosecutor, I had no idea what it would feel like to convict a rapist—to create a little piece of justice on this planet. All along, from the first sex crime I prosecuted to the last day, there were people "in the know" saying that what I wanted couldn't be done.

We have allowed sex crimes to be the one area of criminality where we judge the offense not by the perpetrator but by the victim. There is an essential difference between sex crimes and other crimes, but it has nothing to do with the victims. Most other crime is in response to a need that the offense itself seeks to meet: Some people kill because they are angry; some people steal because they want money. But as each rape is committed, it creates a greater need. Rape is dose-related—it is chronic, repetitive and always escalating.

Rapists cross a line—a clear, bright line. Absent significant, predictable consequences, they are never going to cross back. Too often, instead of consequences, what we give them is permission.

Collaboration is a hate crime. When a jury in Florida acquits because the victim was not wearing underpants, when a grand jury in Texas refuses to indict, because an AIDS-fearing victim begged the rapist to use a condom, when a judge in Manhattan imposes a lenient sentence because the rape of a retarded, previously victimized teenager wasn't "violent," when an appellate defense attorney vilifies a young woman on national TV for the "crime" of having successfully prosecuted a rape complaint, when a judge in Wisconsin calls a 5-year-old "seductive"—all that is collaboration, and it is antipathy toward victims so virulent that it subjects us all to risk.

There are always going to be rapists among us. We need to stop permitting it to be socially and politically acceptable to give them aid and comfort. We need to recognize rape for the antihuman crime that it is. Rape is neither sexual nor sexy—it is an ugly act of dominance and control. We need to start judging sex crimes by the rape and by the rapist—not by the victim.

A rapist is a single-minded, totally self-absorbed, sociopathic beast—a beast that cannot be tamed with "understanding." We need to stop shifting the responsibilities, to stop demanding that victims show "earnest resistance," to stop whining and start winning. And one of our strongest weapons must be fervent intolerance for collaboration in any form.

We need to go to war.

© 1993 Alice Vachss. All rights reserved.

* * * * * *

If You Are Raped

If you are raped it is important to:

- Get Medical Attention.

- Find and maintain a support system (a rape hotline is a good place to start).

- Report the crime to the police.

To aid the police investigation, take these steps to preserve evidence:

- If the rape has just occured, don't shower or bathe before the medical exam.

- Until the police have dusted for fingerprints, try not to touch any smooth surfaces, such as telephones, that the rapist may have touched.

- Save all your clothing and personal items from the crime and tell police what you have.

- Document any injury you suffered, either by photgraph or by showing it to someone you trust.

After the rape, put an answering machine on your phone and let it answer your calls. If the rapist calls (this happens more often than you might think), save the tape. Don't try to trap or confront your rapist on your own. If you might have further contact with the rapist, discuss that with the police before it happens. If you can find the strength—prosecute.

www.alicevachss.com

Copyright © 2007 -

Alice Vachss. All rights reserved.